The Beginning

Charles and Ray Eames married on June 20, 1941, in Chicago. It was a small, intimate ceremony, graciously hosted at a friend’s apartment. Immediately after their wedding, Charles and Ray enthusiastically began the next chapter in their life: California. With no jobs and no concrete prospects on the horizon, the Eameses packed what few belongings they owned into a Ford and drove cross country to begin their lives together.

They arrived in Los Angeles on July 5, 1941. The Highland Hotel in Hollywood became their first home, and despite not knowing anyone in the city, they made friends and connections quickly. One such connection was Richard Neutra, who found the two a home in his newly built Strathmore Apartments— the genesis of the Eames Office. While experimenting within this space, they honed their craft and deep love and admiration for one another as partners in business and life.

“Here we are in Hollywood, right. After many weeks of searching for work with some gleaming future I finally gave up and two weeks ago started work with Metro Goldwyn Mayer [MGM]—all hope for the future is lost but I get a regular paycheck.”

Charles Eames

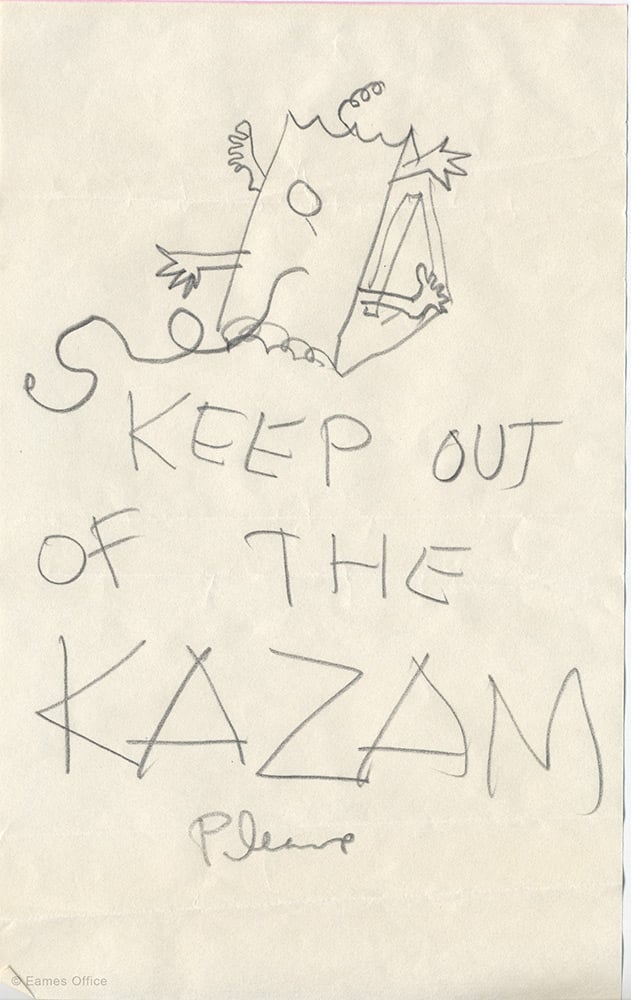

The Kazam! Machine

Through endless hands-on trial-and-error experiments inside their apartment and using a tool they invented called the “Kazam! machine”, Charles and Ray created a process to bend molded plywood into a compound curved shell. The first step of the process involved placing a sheet of veneer into the Kazam! machine mold, and then they added a layer of glue on top of it. They repeated this process five to eleven times. Next, they used a bicycle pump to inflate a rubber balloon after the machine clamped shut, and the balloon pushed the wood against the form. Once the glue set, Charles and Ray released the pressure and removed the seat from the mold, “ala Kazam!—like magic.” Finally, they used a handsaw to obtain the finished shape and hand-sanded the edges to make them smooth.

“It had a curving plaster mold with energy-guzzling electrical coils running through it. Charles long remembered the terror of climbing a power pole by their apartment to poach enough electricity from the transformer to run the Kazam! machine, and the growing conviction he would electrocute himself.”

Eames Demetrios

World War II

In 1942, America was geared for war. Charles’s friend Dr. Wendell Scott, stationed in San Diego, visited Charles and Ray in their Los Angeles apartment, and mentioned that the Medical Corps struggled with a problem: The standard metal splints used to brace wounded service members were causing further injury. The problem stemmed from the metal stretcher-bearers, which amplified vibrations in the brace. Upon hearing this dilemma, Charles and Ray immediately began experimenting with ways to address it; by 1943, the Eameses had made their first Molded Plywood Splint.

The splint conformed to the human leg, offering ideal support through its natural form. In fact, to make the splint, the design duo used Charles’s leg as the model—a harrowing process since removing the cast ripped out all his hair.

Charles and Ray created a great design; however, they ran into a problem that many young designers encounter: Financing. This ultimately led to a partnership with John Entenza and Colonel Evans of Evans Products. With the financial support and a large production facility, the husband-and-wife team was now equipped to handle production on a much larger scale than possible in their Los Angeles apartment guest room. By the end of World War II, it is estimated that 150,000 splints were made and used.

The design led to other wartime molded-plywood work as well, including an airplane fuselage, airplane stabilizer tail, an arm splint, a body litter, and a pilot seat.

“It also was an extremely honest use of materials, wedding the Eames understanding of the limits of the material to the functional needs of the splint. The splints represent a perfect example of utilizing to advantage what the Eameses called the constraints of a particular design problem. Recognizing and working within these constraints was always key to their design process. It was not always easy.”

Eames Demetrios

901

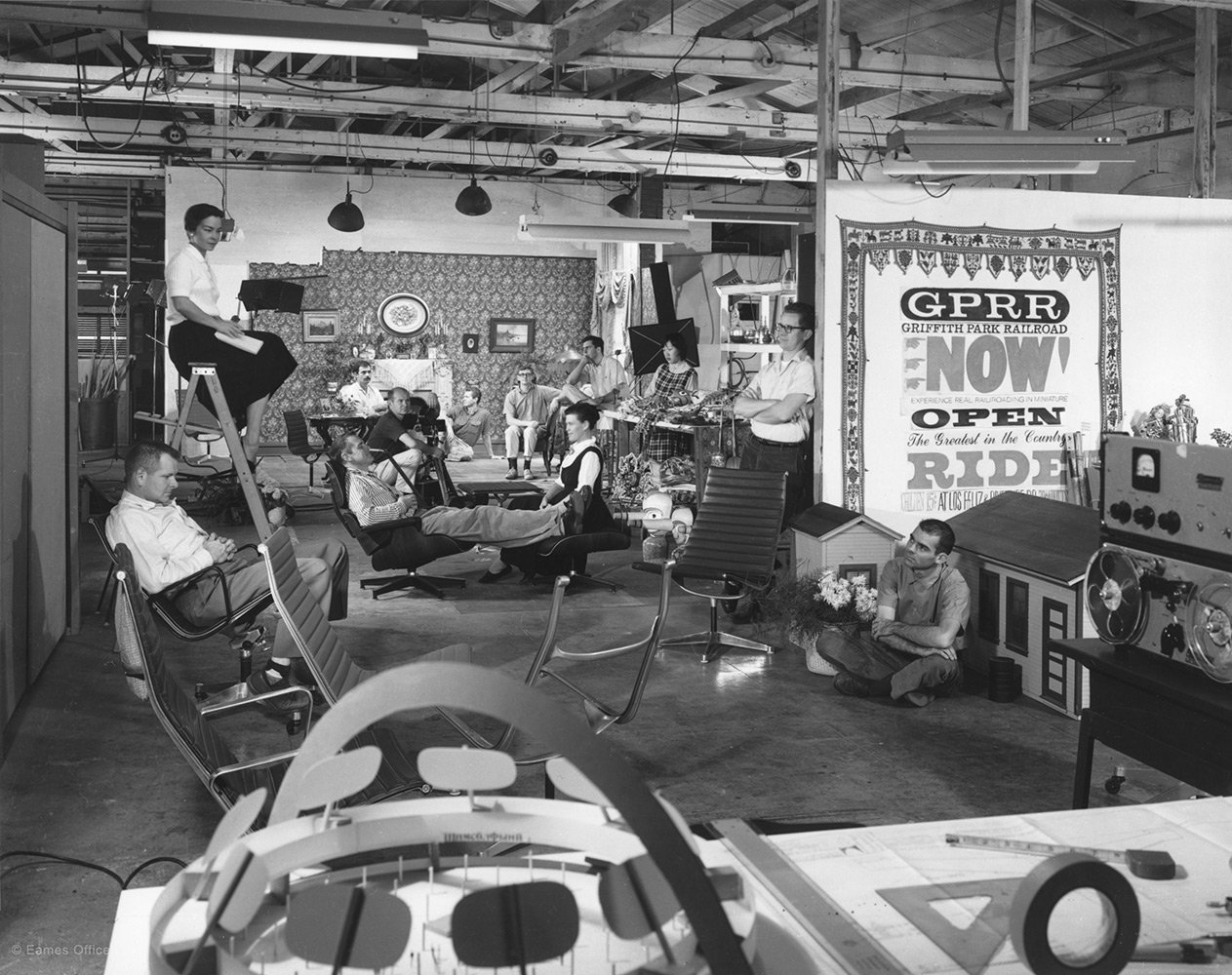

In 1943, the Eames Office moved into a prominent new Venice location on 901 W. Washington Boulevard, famously known as ‘901’. Here, they investigated new molded plywood applications that included glider shells, chairs, children’s furniture and animals, and eventually the LCW (Lounge Chair Wood) in 1946. The industrious walls of 901 served as home to the Eames Office for nearly four decades. Its 20,000 square feet enclosed a circus-like workspace: a playful menagerie—filled with exhibition signage, furniture prototypes, desks, vintage toys, a research library, a film screening room, a pet octopus, and flexible walls—glued together with a work ethic of tightrope-walking precision.

At 901, Charles and Ray and the Eames Office team created furniture classics like the Eames Lounge Chair and Ottoman, designed the Eames House, and made the still groundbreaking scientific film, Powers of Ten. They even held key consulting positions for major corporations such as IBM. The Eames Office made significant contributions to architecture, furniture design, industrial design, manufacturing, and photographic arts, until Ray’s death in 1988.

“There is no Eames style, only a legacy of problems beautifully and intelligently solved.”

Bill Lacey

Today

Now, eighty years after Charles and Ray arrived in Los Angeles, the Eames Office remains dedicated to communicating, preserving, and extending one of the world’s most influential design legacies. Charles and Ray’s work was a manifestation of one broad, all-encompassing goal: positively impacting people’s lives and environments. The design duo left a vital legacy that millions still cherish. Our goal today is both to share that legacy with you and to build upon it. We are comprised of Eames family members and a small but dedicated staff. We work closely with the only two authorized manufacturers of Eames furniture: Herman Miller, Inc. and Vitra International; we curate exhibitions about Charles and Ray’s work and philosophies that travel worldwide; and we collaborate with the Eames Foundation in its goal to preserve the Eames House (a National Historic Landmark visited by thousands each year) for generations to come.