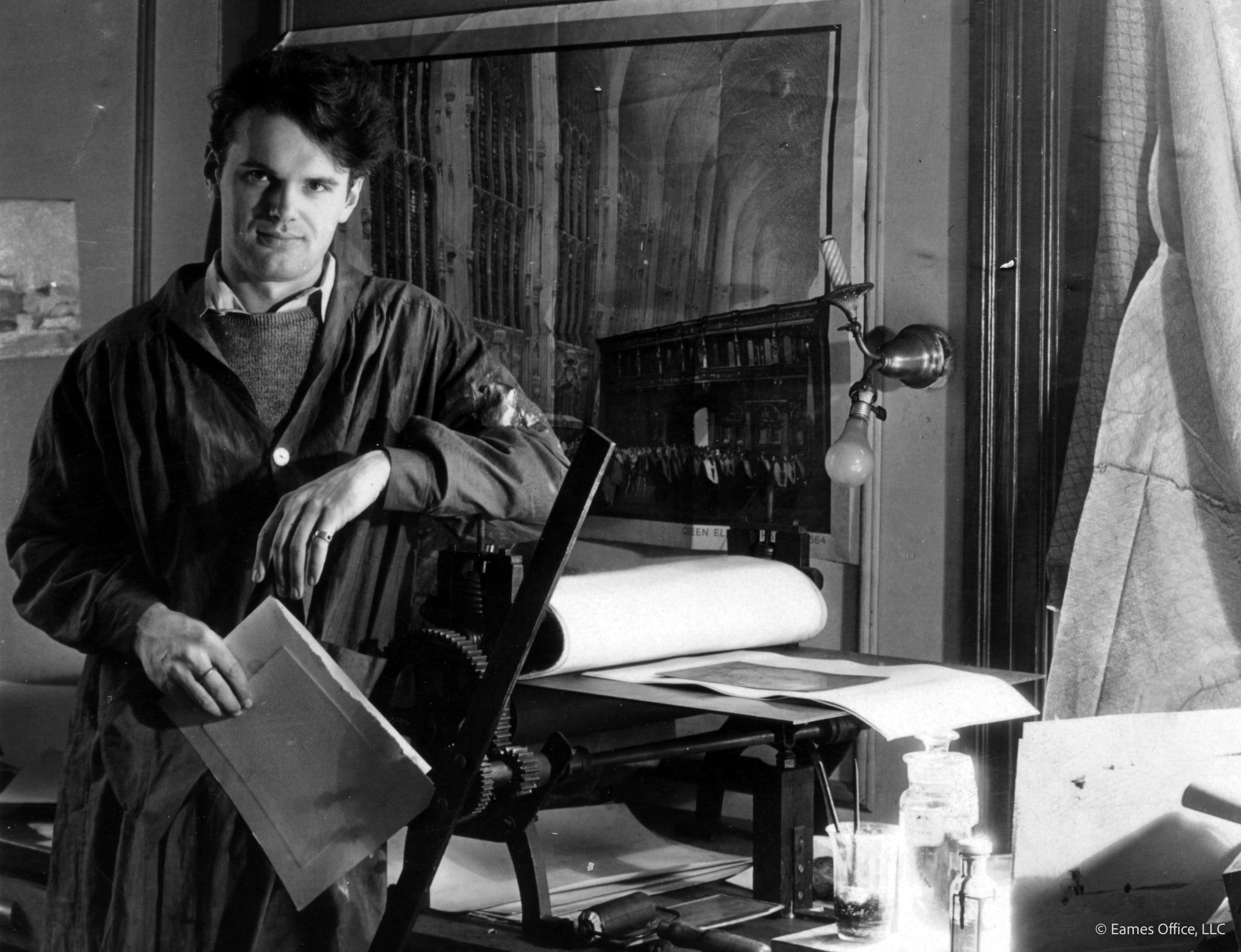

In 1933, during the era of the Great Depression, Charles Eames left his architecture career and young family in St. Louis to travel alone throughout Mexico. He hoped this journey would serve as a compass to personal discovery and to reinvent himself as a creator. Charles committed to returning home only after experiencing both.

Julian Blaustein, a successful Los Angeles film producer and friend of Charles Eames, once recalled what made Charles a unique person and designer: “Charles knew who he was. And that’s a tough assignment right there. . . . I don’t know about you, but I think as you go through life you’ll suddenly become aware that not many people know who they are, what they are about. Are in touch with themselves. Maybe I’m wrong, but I know I find it very difficult among the people I know to find many who can answer that, who can live up to that criteria of personal behavior. I think Charles knew who he was.”

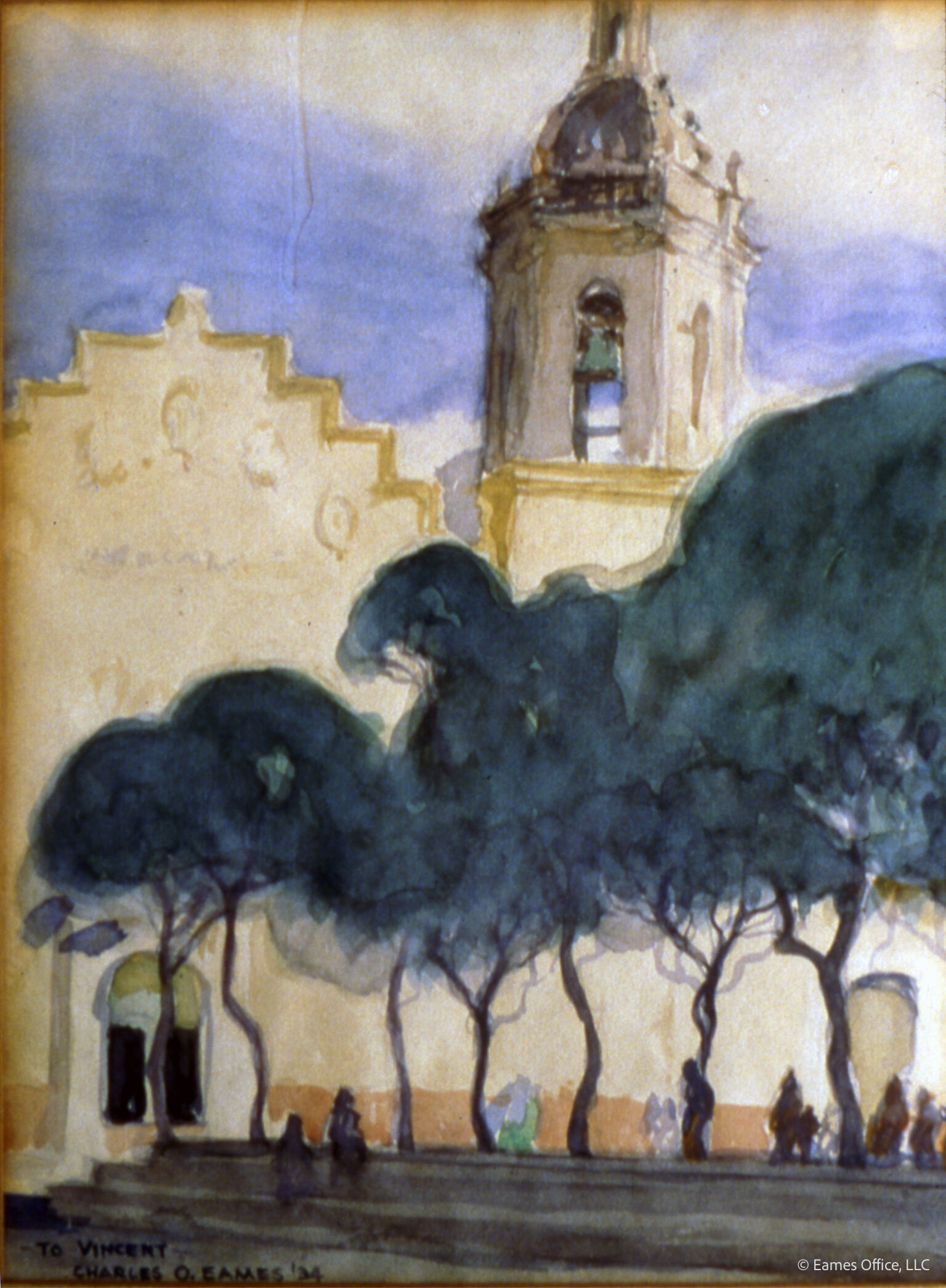

Those who knew Charles personally and scholars who have studied his life would agree with Blaustein’s assessment. This self-understanding, evident in his and Ray’s work and design philosophy, blossomed during his time in Mexico. There, Charles absorbed the vibrant colors and textiles; adobe homes; the big, open sky; distant green hills; and beautiful chapels. The trip was one that Charles desperately needed for his well-being and the advancement of his work.

When Charles left St. Louis for Mexico, he had very little money in his pocket and knew no Spanish, but that didn’t deter him from an adventure. With the clothes on his back and his art supplies in hand, Charles drove an old Ford as far south as he could. He approached the end of an old road in the Mexican state of San Luis Potosi and, from there, traveled by horse and eventually by foot to the more remote villages.

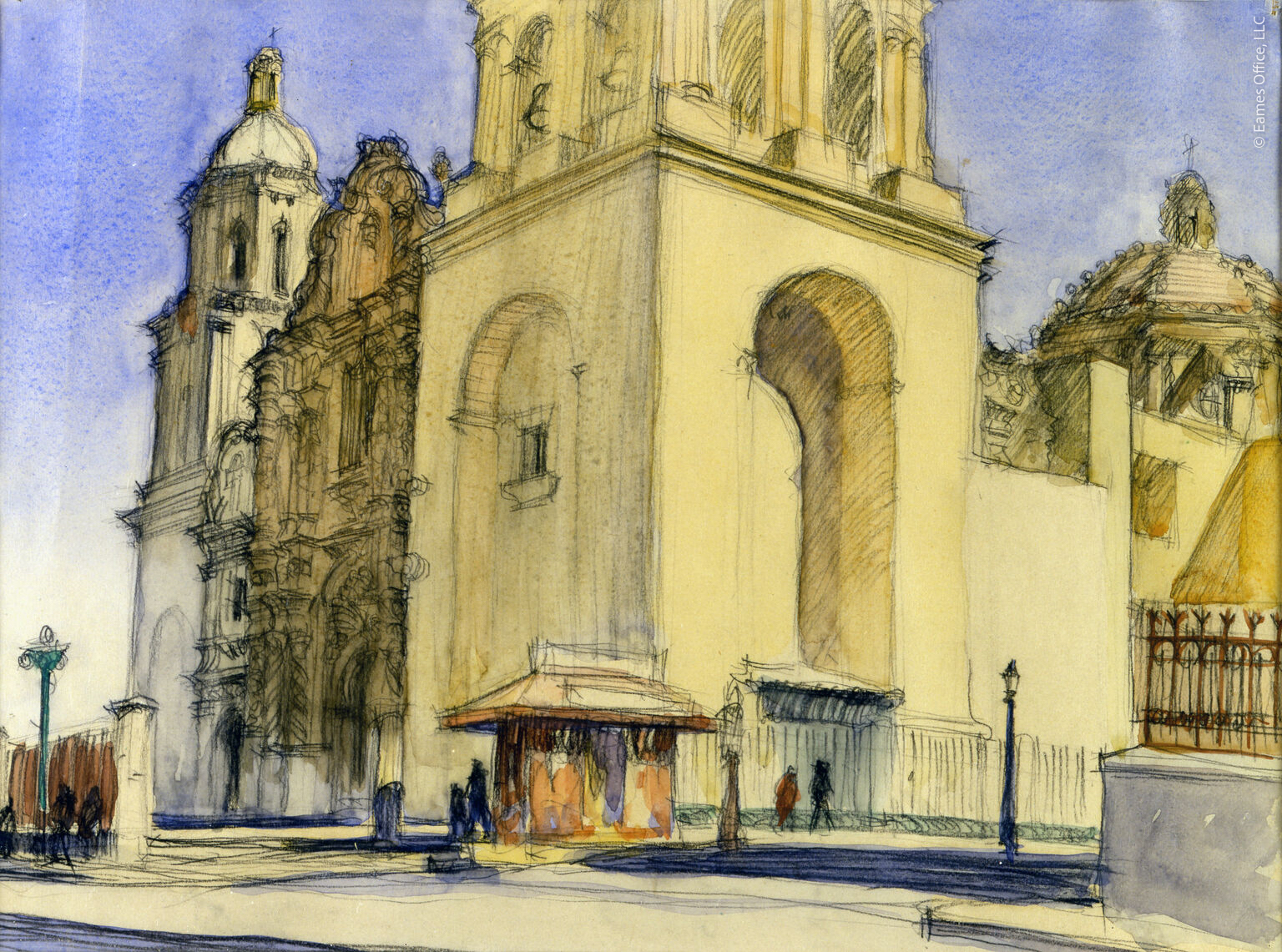

During his ten-month sojourn, Charles had no camera. Instead, he documented his travels through an abundance of watercolor paintings. These works were displayed at the St. Louis Art Museum after he returned home, and many were sold. Fortunately, a few of the paintings still exist today. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch featured Charles’s time in Mexico, in which they discussed the richness of his watercolors:

“Each picture is a memento of a personal experience. A watercolor of a marketplace in Monterrey recalls the day Eames spent in jail for painting it. A view of a little mountain church reminds him of the simple, kindly people who worshiped there and their hospitality to him. A street scene in Saltillo brings back the sounds of fiesta and the fragrance of frijoles and pan dulce. Some of the paintings merely record, of course, occasions when the artist was delighted by a fine harmony of line or mass or a striking arrangement of color in something he saw; but these occasions are important personal experiences to the artist.”

Those experiences shaped Charles. He traded manual labor and, quite often, his sketches and paintings for food and shelter. However, this only sometimes provided steady meals, and he often went to bed hungry.

Charles stayed with locals of little wealth, moved from place to place, and worked when he could. He was absorbing many details and learning all the time. He fondly remembered being the guest of honor in a small mountain village. The town held a fiesta to commemorate Charles’s repainting of an old statue of St. Peter inside a chapel. It is said that citizens thanked Charles for the deed while tears streaked down their cheeks.

Not all of Charles’s encounters in Mexico were pleasant; however, looking back on them, he knew they were all important. As he later noted, any place can be hostile when you have no money and don’t speak the language.

Charles was arrested on two occasions: The first time occurred in Monterrey. As Charles understood it, he was jailed because a local felt his painting of a small marketplace unfavorably depicted the town. The second arrest happened in Linares. He spent a few nights locked up after officials found a book in his possession that contained pictures of ancient Mexican archeological treasures. The officials were concerned that the images showed their country in a bad light. The rats wandering through the dank cells left a lasting impression on Charles, but he always made the best of the situation.

“Another close call for Charles was being rounded up with the citizens of a village for an involuntary smallpox vaccination and watching the dirty needle get closer and closer as it was used over and over again. He got the shot and, fortunately, he and the other recipients were lucky not to have suffered anything worse than a sore arm,” wrote his grandson, Eames Demetrios, in An Eames Primer.

His daughter Lucia long remembered her father’s joyous return home to St. Louis, carrying with him boxes of fabric, colorful folk art, paper mache dolls, and a metal cane whose handle was carved to resemble the head of Satan. “He was no longer mired in the frustrations of St. Louis but instead seemed to be seeking a way to transcend them and to take himself to a new level,” wrote Demetrios. “This is not to say that Mexico was a magic bullet for Charles, but rather that it was the beginning of a process of taking stock of and ultimately changing his approach and situation in life.”

Charles’s friendly and adventurous nature served him well during his travels. One of his colleagues later noted how comfortable he was experiencing other cultures on their terms, which Charles attributed to his time in Mexico. Ultimately, he said that the most important lessons he learned during his trip were that “At least, damn it, you’re not afraid to be broke!” and lastly, “I would never be suckered into a mistake I did not make myself.”