Written by Kelsey Rose

For Charles and Ray Eames, models were as philosophical or scientific as they were diverse. They were generative, in ideas and in the building of human relationships. A model defined concepts of space and transformed a project through innumerable iterations; they offered a multi-layered experience comparable to the cavernous Eames Office in Venice, California. In both the Eames models and the office itself, there was a fine-tuned attention to detail, an exploration of knowledge, a collection of objects arranged to tell stories, and a spattering of people to make the experience come to life. The main difference being the obvious: scale.

“We think of ourselves as tradesmen,” Charles Eames said matter-of-factly during his lecture at the Smithsonian Institution in May 1977. “Mostly, a kind of custom trade. People come to us for things. And mostly, what they come to us for are models, in one sense or another: models before the fact or models after the fact.” Handwritten in the margins of his lecture notes, he defined the two scenarios. “Model before the fact: say an architect’s proposal, showing how something might be structured, if we chose. Model after the fact: say, a scientist’s model of a giant molecule, showing how something may be structured, according to the evidence.” Charles reformulated his description of model making: “By models, I mean ways of structuring certain problems.”

The Eames Office spent a few years attentively designing the IBM Pavilion for the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair. The Eameses and Eero Saarinen served as the architects of the egg-shaped structure, and inside was a marvelous 22-screen theater designed to display the Eames presentation,THINK. Fair visitors entered the IBM scape first to explore an exhibition of mathematics and computing on the ground level, surrounded by colorful, circus-like canopies. For the main feature, the public was invited to sit in the People Wall, a contraption of seated rows that lifted approximately 400 guests upward into the theater’s ovoid shape. A host hovered alone on a platform, greeting guests and calming their nerves about the immense future of technology. Charles said, “The thing about a model is that you can play with it; you can test things out in the model that would be laborious, dangerous, or costly—or just plain impossible—to test in ‘reality.’” The IBM Pavilion was a feat of technology combined with hostmanship’s grace—something that would not have been feasible without a series of models “before the fact.”

In the Smithsonian lecture, Charles continued, “Models are what science is made of, and much of art. A film can be a model; our aquarium film [was an] architectural model before the fact—describing a possible experience and inviting feedback from interested parties.” As an interested party, friend and Newton scholar I. Bernard Cohen arrived in Washington, D.C., and enthusiastically directed a taxi driver to take him to the Eames-designed National Fisheries Center and Aquarium. When he arrived at the supposed location, he was astonished to learn that it never existed. In fact, what he had seen was the Eames Office film proposing the aquarium space. The expanses of glass walls, the people hurriedly digesting information panels, and the tanks of water species placed methodically—these were merely film frames taken of a meticulously detailed architectural model. Often, models solved problems in very convincing ways.

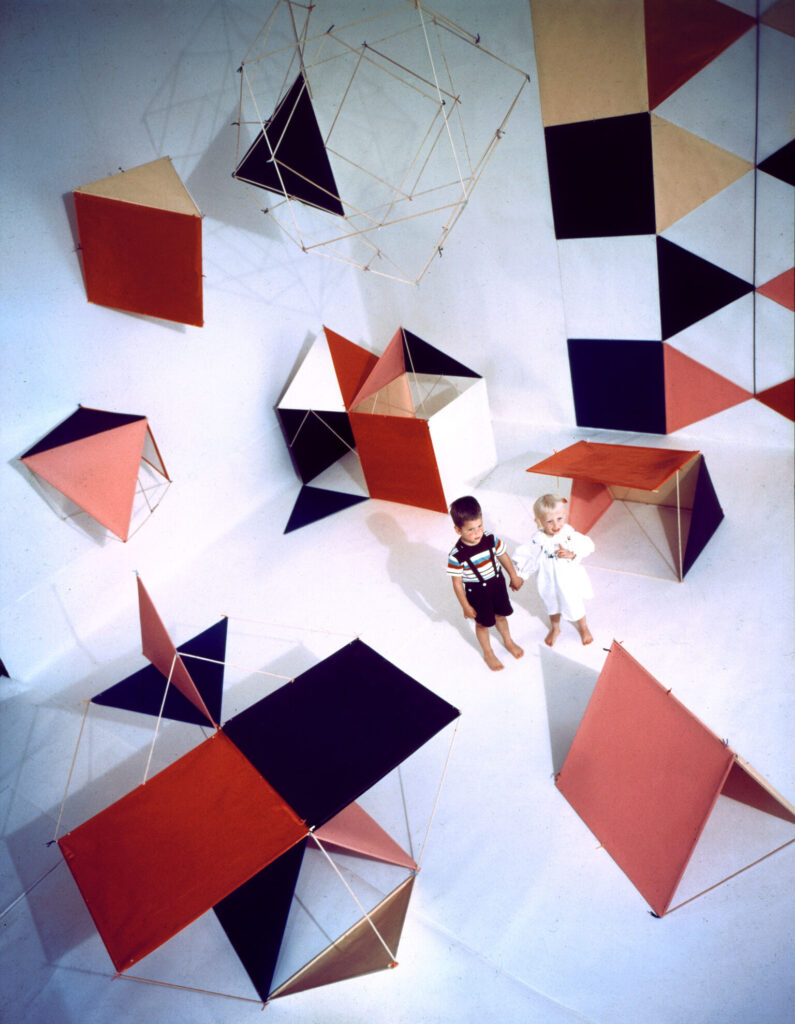

A similar feeling of marvel and confusion is evoked when looking at archival photographs of the models for the exhibition Photography and the City, screens of the Glimpses of the U.S.A. theater, or the architectural mockup of Audrey and Billy Wilder’s unbuilt California home. It’s nearly impossible to separate the scaled-down size from reality. During a Q&A session in a 1954 Eames lecture series at UC Berkeley, Ray addressed the crowd of students, adding her commentary to Charles’s lesson. “Things happen in making a model that never happen in any other way and never happen in the drawings or sketches. In the making of a model you experience the third dimension.” The Eameses were envisioning how to create a complete space and were concerned with the lived experience of their film screenings and exhibitions. They explored how it would feel to be physically within the space, seeing the layers of reality firsthand.

“In the end,” Charles said in the conclusion of his 1977 lecture, “models are what you hand on to the next generation. The ‘culture’ of a time is the sum of its models.” Certainly, the culture of the four-decade production of the Eames Office can be grasped based on the production of its models. It was an oeuvre filled with precision, communication, and a hunger for solving problems.