Additional Information

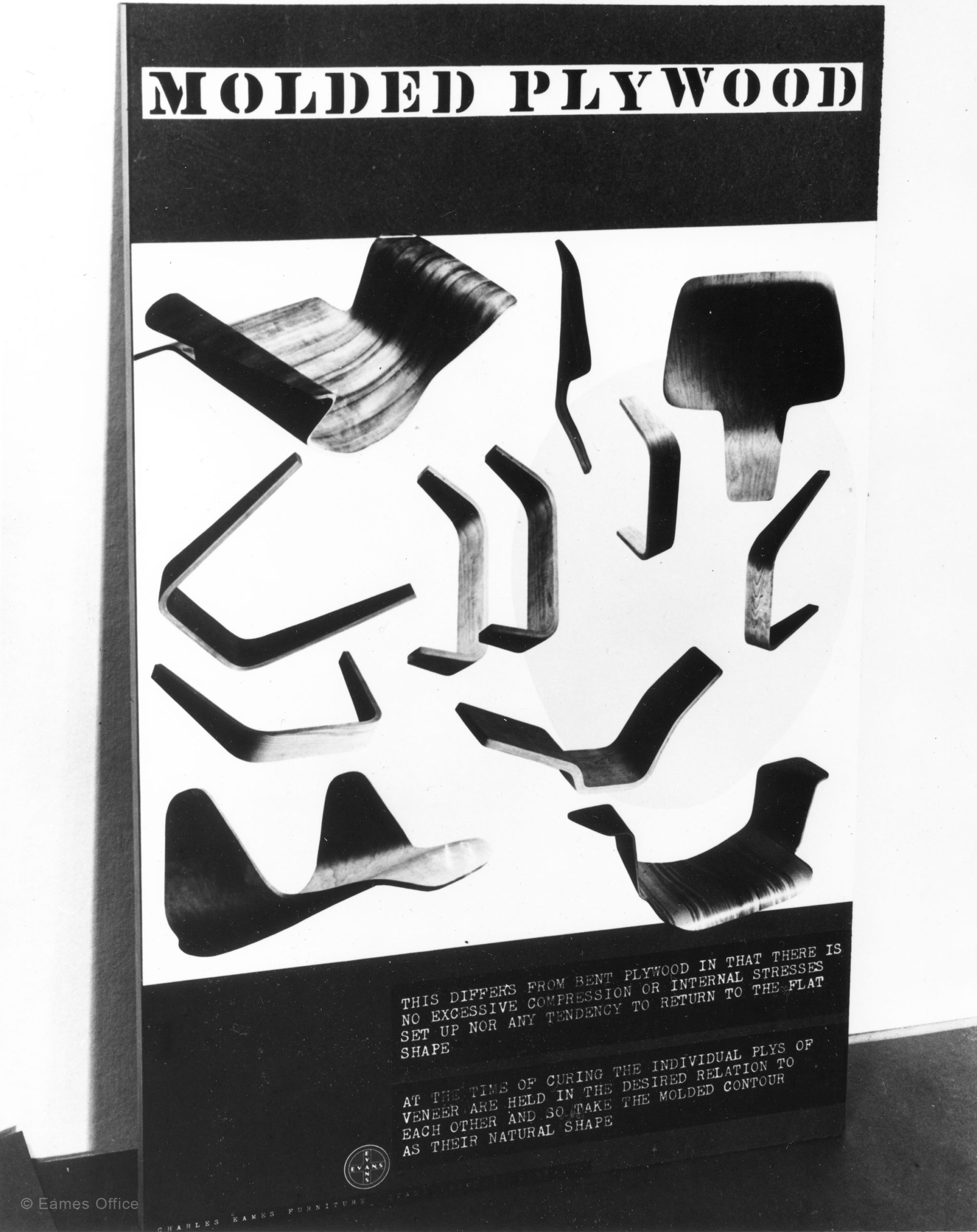

Plywood was not a novel material at this time. Since the 19th century, various designers had used this strong, lightweight, inexpensive form of wood to make furniture. Often, they used it in slab form, and sometimes they molded it in two dimensions, either across its length or its width. But Charles and Ray had a different idea. They knew that if they could mold plywood with compound curves, in three dimensions, they’d be able to provide comfort without thick or heavy padding.

The molded plywood furniture was sturdy, lightweight, and the parts were susceptible to mass production, using the “Eames process,” by which the actual sheets of plywood were formed at the same time as the compound curves were imposed. Using a homemade device, Charles and Ray called the “Kazaam” machine (referencing stage magicians, who put one object in a box and pull out a distinctly different one, Ala Kazaam!), perfected molding in their own residential apartment on Strathmore Avenue in West Los Angeles. The first plywood pieces got their shape from balloons, which Charles and Ray filled with air supplied by a bicycle pump!

The Museum of Modern Art presented the designs to the world in June 1946 as “New Furniture Designed by Charles Eames.”

The New York Times gave it a prominent review, with the sub-headline, “War-Time Developed Techniques of Construction Demonstrated at Modern Museum.”

“Another notable feature of it is the way in which each material has been used to best advantage. The different face veneers used on the plywood have been given a natural finish that shows up the full beauty of the wood. In some cases, the plywood has been treated with a stain in bright shades of yellow, blue or red that penetrates the wood plies, but allows the grain to show through.”

The New York Times

Charles himself could not have said it better. He and Ray believed in the honest use of materials so that “what’s wood is clearly wood, and what’s metal is metal,” and so forth. But they applied dyes to the wood to provide a variety of color options for different interior design schemes. Dyes instead of paint, because paint chipped, and dyed furniture ages well, and dyes don’t conceal the wood grain.

The wood pieces had another innovation: the parts were connected to one another by rubber shock mounts, which provided resilience and flexibility, not usually found in fixed seating.

While, as the Museum’s own press release proclaimed “The chair is king,” the group presented was rounded out with coffee tables, screens. The consistent concept was low cost and high performance.

Of the chairs, Charles himself provided the best technical description described the technical details of their construction in a letter to an engineer friend in 1954.

“The molded plywood chairs are molded from sheets of veneer between heated platens bonded with a thermosetting resin. (Seat and back from five sheets—legs and spine from nine.) Finish of most of these parts is in the form of an impregnating resin sprayed on the surface of the veneer and cured against the platen. Molded parts adhere to the frame by means of the rubber shock mount. The rubber shock mount is a rubber part with a metal insert molded into it. The metal insert is threaded to receive the machine screw. The shock mount is secured to the wood seat and back with a thermosetting adhesive.”

Charles Eames in 1954.

Standardization of parts on similar pieces was accomplished to the point of complete interchangeability. For shipping or storing, similar parts of each chair nest conveniently.

The plywood case goods were a step beyond in quality when compared to the earlier, Organic Design Case Goods. These case goods were also a system, including benches and block construction cabinets, but the finishing details: sliding doors with molded dimples (both attractive, and a feature which increased their strength and resistance to warping) were finer, and box joints were used on the corners. Drawers were molded in one piece, except for the front and back, eliminating steps in the drawer construction.

They devised two types of tables, round and rectangular, with tops of plywood and either bent plywood or bent steel legs. The round tables, which we still make today, had a feature which was not only decorative, a molded top, which also, through the act of molding, resulted in thin wood tops that were less susceptible to warping. Table legs were detachable for less expensive shipping and ease of storage.

The dining tables, available in rectangular form and square (to be used as a card table or a dining table extension), featured legs that could be nested once they were detached for shipping. Another dining table had folded metal legs. Finally, there was a three-legged coffee table with molded sides and three metal legs. Restraint was the hallmark of these designs. When three legs could do, why would they use four?

This new business relationship dictated what happened next. Herman Miller specifically took only some of the group: the chairs, the dining or desk height DCW and DCM, the lounge height chairs, the LCM and the LCW, the round coffee tables, and the bent plywood leg dining tables.

As attractive as the Eames case goods were, Herman Miller had other considerations. They decided to have their design director, George Nelson, provide case goods for what was to be called “The Herman Miller Collection” which launched in 1948. Thus, this early incarnation of Eames case goods did not go into production and have yet to be produced.

Explore Similar Works

Related Products

Browse a curated selection of Eames Office products we think you’ll love