Additional Information

In their lifetime, Charles and Ray succeeded in making one-piece “surfaces to receive the body” only twice: with molded plastic and with molded and welded steel wire. The molded plastic chairs came first, and it’s interesting to note that the form of these chairs was first worked out in metal, not plastic, because Charles and Ray were “material agnostic.” Charles and Ray didn’t set out to make metal or plastic, or wood chairs. Instead, they set out to meet the need for certain types of furniture, and they had no preconceived ideas as to what materials would work best—they sought out the best material, with the need foremost in their minds.

A 1949 Museum of Modern Art competition gave a jet assist to the Eames furniture development. As previous award-winners, the Eameses were granted $5000 by MoMA to lead a research group into new low-cost furniture. The result of their process was what they entered into the competition: one-piece shells, in both arm and armless forms, with a great variety of structural options, to provide the “proper relation to the ground” for the shells, constructed of stamped steel coated in neoprene to moderate the surface temperature of the metal. The Eames entries took second place. The judges mainly complimented the system of bases: which included standard four-legged bases, rocking chair bases, a low base made out of steel wire, and even a contract base of cast aluminum.

At this point, on the third anniversary of their relationship with Herman Miller, the Eameses were for the first time met with resistance. Herman Miller balked at spending $80,000 for a steel stamping press for a design that had no precedent in the marketplace. So Charles and Ray turned to another wartime technology: fiberglass molding. Fiberglass was only invented in the 1930s, and its use during World War 2 was restricted to military applications. For example, it was used on military airplanes in the form of molded cones called “radomes,” to protect delicate electronic equipment, such as antennas, from the elements.

For proof of concept, the Eameses hired a fiberglass fabricator named John Wills to make two models of their arm shell shape in fiberglass. One of those two models is still with us today, and you can see it on display at The Henry Ford Museum, where Charles and Ray are featured with their own exhibit, contextualized with other great inventors like Luther Burbank, the Wright Brothers, and Thomas Edison.

With a full-size, three-dimensional example to test out, Charles and Ray were confident that fiberglass would be even better for their shell chairs. It was naturally resistant to extremes of heat or cold, meaning they wouldn’t need to coat it! Rubber shock mounts, which worked so well with the molded plywood group, could likewise be used with these shells to attach the legs to the shells while providing added flexible comfort. They drafted two people, Irv Green and Sol Fingerhut, of Zenith Plastics, their production partners. When Irv and Sol met Charles and Ray, they had only ever made radomes for airplanes. However, Green and Fingerhut were so eager to get into the furniture business and were so taken with these designs that they not only proposed a $5000 cost of machinery; they agreed to pay for half of the cost themselves. Herman Miller paid the other $2500.

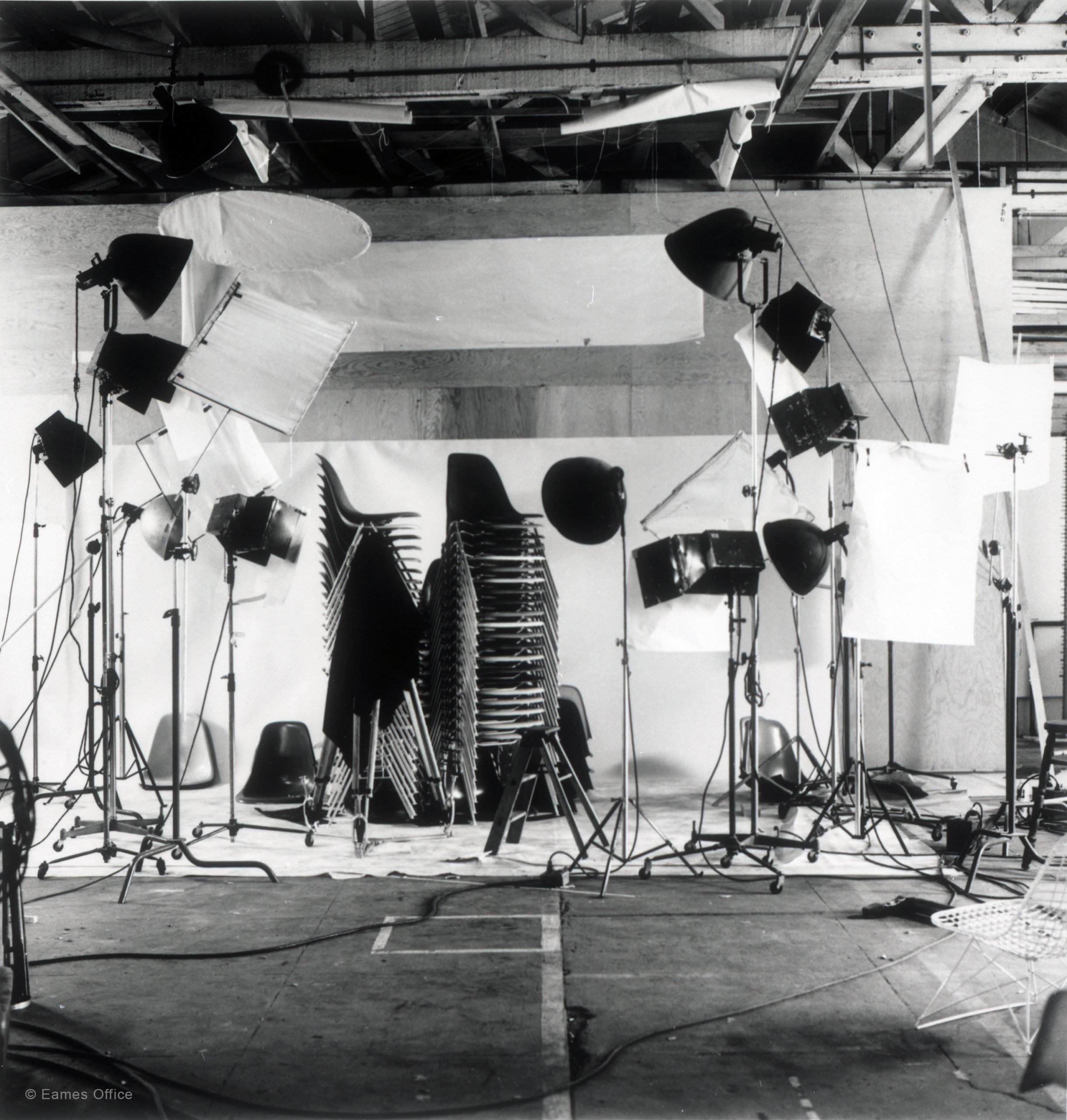

Charles Eames described their innovative technique for molding the plastic shells in these words: “The reinforced polyester was a special technique developed for areas that demanded a high-performance material. Essentially this meant the aircraft industry that could afford big investments for the development of material and tooling. Our object was to make this high-performance material accessible to the consumer in a chair that would ultimately give it a high performance per dollar. The problem wasn’t so much one of form. “The real problem was to make this essentially industrial material available at the consumer level. At first we had very clear ideas of the kind of surface we wanted to maintain, but eventually we realized that anything would do just as long as it was uniform. Uniformity, uniformity…eventually we realized that this was what we were striving for, and that actually it was the toughest thing to get.”

The contract for the first production chairs was signed in November 1949, and to an audience of business people, the chairs were first shown at the Chicago Merchandise Mart in January 1950. The chairs had their big public debut when they were presented with the other prize winners of the Low-Cost Furniture Competition. By the time of the opening, both the catalog and the name of the exhibition had evolved. The show and book were called “Prize Designs in Modern Furniture.” One suspects that in 1950, retailers were reluctant to advertise “Low Cost” furniture. The New York City retailer who presented the designs for sale was “Sachs Quality Furniture,” and their sale coincided with the museum exhibition.

“Airplane Plastic Chair by Charles Eames.”

1950’s Sachs Advertisement

While plastic is everywhere in our lives now, plastic furniture of this type had never been offered to the public. The text of the Sachs newspaper ad provides some insight into the era of this big event in world furniture history. Charles stated: “When we first introduced this revolutionary new plastic and fiberglass chair to New York, we thought it would take plenty of time to catch on. We thought only the ultra-modern homemakers would go for such advanced designs. How wrong we were! Hundreds of homemakers came in to see this wonder chair.”

They ooh-ed at the smooth, cool, lustrous texture of the fiberglass. They ahh-ed at the amazing comfort of this ingenious chair (rubber shock cushions between the seat and legs give it remarkable resiliency for a non-upholstered chair). It actually “gives” and cradles the body with every change of position.

In the first year of production, the fiberglass chairs were available in only three colors: greige (grey-beige), elephant hide grey (light black), and parchment. The colors are an Eames design story in and of themselves. Before Charles and Ray Eames had the idea to make furniture for the home out of fiberglass, fiberglass has mainly been used in places where its appearance didn’t matter. “Radomes” on military airplanes were made of the “natural color” of the fiberglass mixture, with no added pigments. To make the most useful furniture, Charles and Ray spent dozens of nights at the Zenith factory, mixing up different combinations of pigments, to achieve colors that they felt would work in most home or office environments. At launch time, they had only three integral colors ready, the ones highlighted in the Sachs ad. Eventually, in later years, the Eames fiberglass chairs were offered in as many as 30 different colors.

Charles and Ray Eames embraced new technology when it meant that they could provide more products, for less money, to more consumers. Because the technology of making chairs in hydraulic presses was so new, Charles went out of his way in a letter to an engineer friend to describe it.

“The molded fiberglass chair is made from a fiberglass preform. The fiberglass is short pieces of glass fiber roving which have been blown into a cyclone and pulled up against the preform screen by air, which exhausted through the screen. The preform is then set between male and female dies, a predetermined amount of polyester resin poured into the preform and the matched dies, then closed on this combination, and the resin is forced between the fibers and cured at a temperature of 250 degrees F. for a time duration of five minutes. The finish can be seen as an integral part of the chair and is not later applied, but rather forced around the glass fibers as molded.”

As distinguished from a painted or otherwise applied finish, this idea of integral is another consistent thread in Eames’s work. The Eames’s preference for integral finishes has to do with their objective of a long life of service and performance for anything they design. An applied finish, especially a painted one, can chip away over time. An integral finish, if it ages at all, ages gracefully.

Charles once explained that designers seek solutions; they don’t necessarily “create” solutions. In this, the best designers have a lot in common with the best scientists. There is precedence in nature for hard, shaped surfaces to support an organic form: seashells. Like seashells, the shape of Eames molded plastic shells is enduring and timeless, the product of years of development, which resulted in the forms of 1950.

In the twenty-first century, we’ve taken those same timeless forms and rendered them in new materials. First, in 2006, we worked with Herman Miller to bring out these same forms in polypropylene, a material lighter and weight and more environmentally friendly than the original fiberglass formulations. These have proven to be a big hit in contract settings, where they must endure a lot of wear and tear. In 2012, using a new proprietary technology sourced by Herman Miller, we achieved a dream that had eluded Charles and Ray: a one-piece molded wood chair.

The authentic, single-shell form of the Eames Molded Wood Chair is achieved through a process of 3-D veneer manufacturing technology that enables wood veneer to be molded into complex curves—thus completing the Eameses’ decades-long endeavor to create a wood shell chair.

The side chair is available in a variety of wood finishes, all of which pair with a range of base options, the same bases available for our other “shell” chairs, including the wire chairs.

Explore Similar Works

Related Products

Browse a curated selection of Eames Office products we think you’ll love

![CH_PDp(Db)111[256a]](https://www.eamesoffice.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/CH_PDpDb111256a-scaled.jpg)